This decade in Elon

As the decade has gone on, the occurrence of Elon Musk events has increased, and a brief glance back at the timeline shows this isn’t just a psychological phenomenon: Elon really is Elonning more often.

Cast your memory back, if you will, to the reaches of Very Recent History. At the beginning of this decade, Tesla had just one car: the Roadster. SpaceX had not yet secured a commercial crew contract for NASA. Neuralink, the company attempting to create commercialized brain-machine interfaces, didn’t yet exist, nor did the Boring Company, Musk’s tunneling concern.

Back then, Musk was still best known for getting fired from PayPal. And while Tesla had built the Roadster in 2008, wowing car nerds with its acceleration, it was still a niche product. Plus, both SpaceX and Tesla nearly went bankrupt in 2008. So while it’s possible Musk was saying as much weird shit as he would say later on, he didn’t have the same kind of spotlight on him; the stakes were lower.

Then, in 2010, three significant Elon events occurred, which would set the stage for more to follow: in June, SpaceX launched the first version of the Falcon 9, and Tesla went public. In October, Tesla took occupancy of the former NUMMI factory in Fremont, California.

From here, the pace of Elon-related activity would only accelerate. Some of this was inevitable: SpaceX and Tesla were taking on new business challenges, launching new products (literally, in SpaceX’s case), and becoming more popular. That meant Musk’s pronouncements took on a new weight and received more media coverage. It also meant that Musk was trotting himself out more often: because Tesla doesn’t advertise, promoting the brand meant Musk had to serve as a celebrity hypeman.

SpaceX

After the initial 2010 launch of the Falcon 9, SpaceX became the first private company to dock at the International Space Station in May 2012. The Dragon spacecraft went on to be a major way that NASA delivered supplies to the ISS. By April 2015, SpaceX had flown seven missions to the space station. In 2014, NASA deepened its relationship with SpaceX, contracting the company to develop a version of its Dragon capsule for people.

Things began shifting in 2015. In December, SpaceX landed its first rocket. Before this, there’d been some skepticism about Musk’s idea of a reusable rocket as a possibility at all — and some skepticism still exists about whether it’s a reasonable cost-cutting measure. (Refurbishing a rocket is expensive.) But after this initial landing, SpaceX so routinely landed its first stages that people began to take them for granted. In December 2017, SpaceX launched and landed its first reused rocket. In 2018, SpaceX flew the first Falcon Heavy, sending Musk’s Tesla Roadster into orbit.

The launches did not go entirely smoothly. In June 2015, a Falcon 9 exploded a few minutes after launch when a strut failed in the rocket’s upper stage liquid oxygen tank. The second rocket blew up during fueling in September 2016 — and this time, there was a whiff of scandal, as sabotage was considered among the reasons for the explosion. This explosion was ultimately chalked up to a problem with the helium tanks, carbon fiber composites, and solid oxygen. The two explosions delayed SpaceX’s other planned launches as the company investigated to determine their causes. There was a third explosion in 2017, but this one didn’t slow the slate of flights since it was just an engine on a test stand. A fourth explosion happened in April 2019 when a test version of the Crew Dragon — the SpaceX vehicle meant for people — blew apart. Leaky valve, propellant, boom.

In September 2016, Musk presented plans for his proposed attempt to create a Mars settlement. In an hour-long presentation — here’s a truncated version — Musk introduced the Interplanetary Transport System: a spaceship and rocket. (There were, obviously, a lot of unanswered questions left after the presentation.) This system was updated in 2017, and Musk said he planned to put all of SpaceX’s resources into the Mars mission; this does not seem to have happened yet.

As SpaceX was flexing, the rocket launch market began to change. The commercial market for launching satellites into geostationary orbit was “very soft” in 2017 and 2018, SpaceX president Gwynne Shotwell said. That threw a wrench into SpaceX’s plans. In financial documents dating from 2015, which were obtained by The Wall Street Journal, SpaceX had projected more than 40 launches; there were actually 20. In 2019, SpaceX had estimated 52 launches — one every week — and there were, in fact, 12, with two more scheduled before the end of the year.

The slowing market for commercial satellites — and the smaller number of rockets needed to launch them — meant that SpaceX needed to retool its plans. Now, since SpaceX is a private company and doesn’t have to make its planning public, I can only speculate about what that entailed.

It may be why SpaceX dipped its toe into space tourism. In 2018, Musk announced that Yusaku Maezawa, a Japanese billionaire and founder of Zozotown, Japan’s largest online clothing retailer, will be the first private customer to ride around the Moon on the company’s future ship, which was rebranded from the Interplanetary Transport System to Starship. But betting on the billionaire might not be such a good idea since he tweeted in May that he was broke. SoftBank’s Yahoo Japan has since acquired Maezawa’s Zozo, an online fashion retailer, for $3.7 billion. So, presumably, the trip is still on.

Space tourism isn’t SpaceX’s only moneymaking strategy. SpaceX is also venturing into the realms of telecommunication with its Starlink venture, which may begin offering broadband services as early as next year. (Take that projection with a grain of salt: in 2011, Musk said he’d put a person in space in three years. It is 2019, and a human has yet to fly aboard a SpaceX rocket.) Starlink is a proposed constellation of at least 12,000 satellites in low Earth orbit, though the company has asked for an additional 30,000 satellites. Astronomers have some misgivings about this effort.

SpaceX launched 60 of those satellites in May, and some of them have failed; a second launch in November sent up 60 more. The 2015 SpaceX financial estimates The Wall Street Journal got ahold of projected the Starlink business would dwarf the rocket launch business — and now, as a result of the slowed pace of launches, Starlink seems like a make-or-break business for SpaceX. (Again, this is all guesswork; it’s sort of hard to figure out what’s going on financially with a privately traded company.) In any event, in October, Musk tweeted that he was going to send a tweet using the Starlink system. “Whoa, it worked!!” he wrote.

If Starlink is successful, then the 2020s will truly be a new era for SpaceX: it will be a consumer business.

Tesla

Tesla’s initial public offering was in June 2010; the company raised $226.1 million during the first IPO of an American carmaker since Ford went public in 1956. Tesla badly needed the cash. The company had teetered on the edge of bankruptcy during the 2008 financial crisis. It had only one car, the Roadster, and it had never made a profit. This would all change over the course of a decade, and thanks to the ready availability of information on publicly traded companies, Tesla’s travails would prove easier to track than SpaceX’s.

For better and sometimes worse, this decade was the decade of the Tesla factory in Fremont, California. Every Tesla car built this decade came from Fremont. Without that plant, it seems unlikely Tesla would have been able to begin its deliveries of the Model S (in November 2012), the Model X (September 2015), or the Model 3 (July 2017).

The Model S, priced between $57,400 and $77,400, was supposed to go into production in 2010, but production didn’t actually start until 2012. These kinds of delays would be a common refrain: the Model X, an SUV that started at $132,000, was introduced in February 2012 and was initially scheduled for production in early 2014; deliveries started in September 2015.

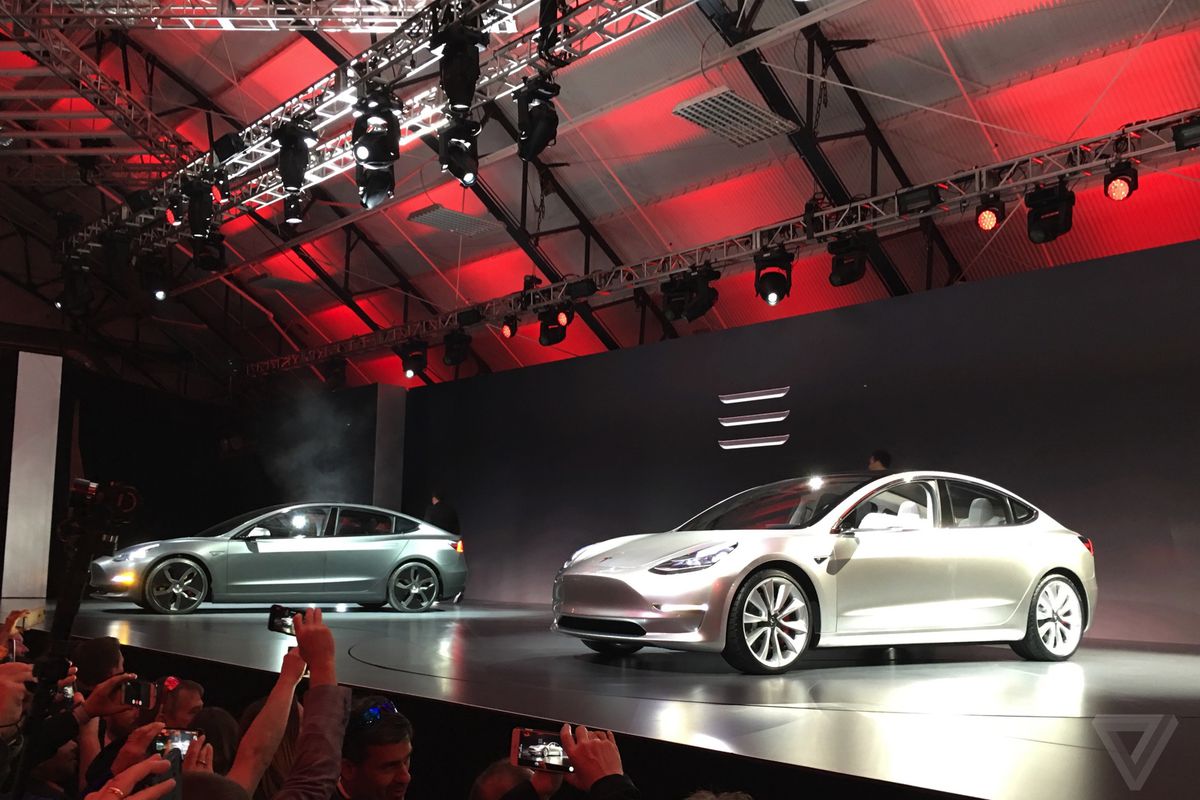

Then there was the matter of the Model 3. At its unveiling in March 2016, Musk said the Model 3 would be his affordable, mass-market electric car: the base model would cost $35,000. A week after Tesla started taking orders, the company said 350,000 people had reserved the cars.

That raised some manufacturing questions since the Fremont factory had delivered fewer than 51,000 cars total in 2015. Part of Musk’s initial plans for making the Model 3 involved turning the factory into an “alien dreadnaught,” a machine to build cars, he said in a 2016 earnings call. This did not turn out as planned. In 2018, Musk admitted that Tesla relied too much on robots to build the Model 3s, which is why there were manufacturing delays leading up to the car’s introduction in July 2017.

But even after the Model 3 began production, there were bottlenecks. The Fremont factory was bursting at the seams. The catch-all for this, of course, was “production hell.” So Musk… built a tent in 2018. And that tent became another assembly line.

The Fremont plant was also where workers complained about their conditions. According to reporting from The Guardian, ambulances had been called more than 100 times to the Fremont factory between 2014 and 2017 for fainting spells, dizziness, seizures, abnormal breathing, and chest pains. “Hundreds more were called for injuries and other medical issues,” the report said. Another report from 2017 showed that Tesla workers were injured at a rate of double the injury average. Workers in the tent in 2019 said they were pressured to take shortcuts to hit production goals.

Worker unrest meant the possibility of a union arose; unions are common in car manufacturing, after all. A Tesla employee, Jose Moran, wrote a 2017 Medium post complaining at length about working conditions and saying that’s why he thought Tesla should unionize. At first, Musk claimed Moran was an employee of the United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW), rather than Tesla. By 2018, the National Labor Relations Board was involved, reviewing Musk’s tweets (“Why pay union dues & give up stock options for nothing?” he tweeted in May 2018), among other evidence. In September 2019, Tesla and Musk were found to have violated labor law.

Even as Fremont was the primary Tesla site, Musk’s manufacturing ambitions led to several new factories. The unfinished Gigafactory 1 opened in Nevada in July 2016; it was 14 percent complete at the time. The August 2016 acquisition of SolarCity would give Tesla what would later be known as Gigafactory 2. In January 2019, Tesla broke ground for the Shanghai Gigafactory; by October, Tesla claimed it was ready for production. A fourth Gigafactory is planned for Berlin.

The Gigafactories have also given rise to some controversy. In 2018, Business Insider reported that batteries at the Gigafactory were getting scrapped (or reworked) at a rate of 40 percent. The man who was blamed for the leak was an assembly line worker named Martin Tripp, and Musk characterized him as engaging in “extensive and damaging sabotage” in an email to staff, Bloomberg reported. Litigation between Tripp and Tesla is ongoing. A former security manager named Sean Gouthro alleges in a whistleblower report with the Securities and Exchange Commission that Tesla behaved unethically in its search for the leaker. Tesla maintains it terminated Gouthro for poor performance.

Then there’s Gigafactory 2. New York (the state, not the city) spent $958.6 million on the factory and wrote that down to about $75 million — though that figure doesn’t capture the plant’s economic value to the surrounding area, The Buffalo News reported. Some workers there have said they found the work environment hostile.

Of course, the 2016 SolarCity acquisition was more than just a factory; it was a new line of business and possibly a conflict of interest. (The shareholder lawsuits are still out there, and they allege SolarCity was going broke before the acquisition, and “conflicted fiduciaries” negotiated an inflated price on SolarCity shares. Tesla and Musk have denied these claims.) SolarCity’s founders are Lyndon and Peter Rive, Musk’s cousins. Musk was chairman of both companies when Tesla bought SolarCity; he was also SolarCity’s largest shareholder.

At the time, SolarCity was the biggest player in residential energy. Since then, it’s been passed by Sunrun and Vivint Solar, Marketwatch reported in June. Maybe that was because most of Tesla’s resources were being sucked up by Model 3 production, as Musk said in a deposition. (Tesla has said that the number of batteries supplied by Panasonic is a “fundamental constraint.”) Maybe people got tired of waiting for the Solar Roof, a product announced by Musk at the same time as the acquisition — which still hasn’t seriously surfaced as a consumer product three years later. It is perhaps also worth mentioning the hair-raising litigation from Walmart — now dropped — about a series of solar panel fires.

Energy storage and solar panels may be a Tesla business we see grow over the course of the next decade or so. After building the largest battery in the world — in Australia — to help buttress the electric grid, Tesla may soon be building an even bigger one in California. The company has also introduced a new industrial storage pack. In California, several energy companies have been cutting power to avoid wildfires, and those blackouts are unlikely to stop anytime soon. That may provide an opportunity for Tesla’s consumer energy business as well.

At times, the pressure from Tesla appeared to be getting the better of Musk. The most significant stress period occurred in August 2018. On August 7th, Musk tweeted: “Am considering taking Tesla private at $420. Funding secured.” By August 24th, Musk had abandoned this plan. Then, a month later, the SEC sued him over the “funding secured” tweet: “In truth and in fact, Musk had not even discussed, much less confirmed, key deal terms, including price, with any potential funding source,” prosecutors wrote in the complaint. Two days later, the suit was settled: Musk would step down as chairman of Tesla, and both he and Tesla would pay $20 million fines. Also, there was a provision about tweeting, which got relitigated this year because Musk will never log off.

In any event, Tesla carved out its first back-to-back quarterly profits in the last two quarters of 2018. In the second quarter of 2019, Tesla made and delivered the most cars in its history, though the company still posted a loss for the quarter. It made its first profit in 2019 during its third quarter. One consistent theme throughout Tesla’s existence has been skeptics who’ve said the business doesn’t seem sustainable. Despite the naysaying and some close calls, Tesla is still in the ring. With the Model Y (a compact SUV) and Cybertruck coming in the next decade, Tesla has the opportunity to prove naysayers wrong — or undergo another production hell. Strap yourself in because, whatever happens, it’s likely to be a fascinating ride.

Other businesses

Musk launched two new ventures this decade: Neuralink, a company for brain-machine interfaces, and the Boring Company, a tunnel-boring venture. The two companies appear to have much less day-to-day attention from Musk. At his Twitter defamation trial in December 2019, Musk described Tesla and SpaceX as occupying 95 percent of his time. Still, both ventures are worth mentioning at least in part because they seem to expand Musk’s science fiction-influenced worldview.

Neuralink was founded in 2016, about a decade after the first clinical report of a person using a brain-machine interface to move a cursor on a screen. Neuralink was publicly unveiled in 2017, and Musk gave more details on the company’s ambitions: to give people who are disabled a way to command computers as a compensatory aid, allow for telepathic communication, and graft human thought onto AI systems.

Well, Musk usually dreams big.

In 2019, we got some more details on the design of the Neuralink technology: flexible threads to be embedded in the brain. Also, a monkey has used the technology to “control a computer with its brain,” Musk announced, to the surprise of his team. The company is still in early stages, and biotechnology usually takes more than a decade from initial research to sale on the market, with lots of studies in between to help characterize the technology.

The Boring Company is moving faster, probably because it doesn’t require brain surgery. In January 2017, Musk tweeted about Los Angeles traffic “driving me nuts.” He said he had a new venture in mind: the Boring Company.

Musk wasn’t kidding. The Boring Company began as a hole in the SpaceX parking lot. Financed by hats and Not-A-Flamethrowers, plus an equity raise, the tunnel-boring concern debuted its test tunnel with a party in December 2018. At that time, three other potential projects were in the works: one for a Dodgers Stadium in LA, one in Chicago, and one in the DC area. (A potential tunnel on the west side of LA was canceled after a group of residents and community groups sued.)

In 2019, Chicago got a new mayor, and, suddenly, the Boring Company project was placed on the back burner. But Las Vegas, which is no stranger to quixotic transit projects, stepped into the breach: the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority entered into a $48.6 million contract with the Boring Company to build a “people mover.” That project broke ground in November 2019, and it’s expected to be completed by CES 2021.

Elon himself

Musk’s Twitter account exists in an ongoing state of epistemic uncertainty. Sometimes he tweets things that seem like jokes and aren’t — a lot of these things pertain directly to the Boring Company, which seems to be something of a catch-all for Musk’s whimsy — and sometimes he really is just joking. (I don’t think he’s going to build a volcano lair.)

There are, however, some more general things that Musk was up to during the 2010s, of which, the most significant were his involvement with OpenAI and the hyperloop.

The hyperloop was first revealed to the public in 2012, with more details following a year later. Musk said publicly that he had “no plans” to build his design, but that didn’t stop a lot of other people from forming hyperloop companies. The basic plans called for “pods” traveling at 800 miles per hour to send people quickly from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Musk did build a test track that’s about a mile long outside his SpaceX headquarters, and in 2015, he began hosting a pod-racing competition for students. These events seem to be largely hack-a-thons, which may also serve as recruiting pools for engineering talent. Next year, Musk says, the test track will have a curve. And an actual hyperloop may eventually be built in India.

There is also the matter of artificial intelligence. While many AI experts have come to believe that artificial intelligence is likely to be limited, Musk has warned about hyper-intelligent, human-hating AI: “we are summoning the demon,” he said in 2014. (As of 2018, he’s still anxious about it.) So Musk was one of the founders of OpenAI, which is meant to build friendly AI. The foundation initially raised about $1 billion from various tech companies and executives, including Musk. In February 2018, Musk stepped down from the foundation since there might be some conflicts between his attempts at Tesla to build self-driving cars and OpenAI’s work, but he said he will remain a donor. The CEO remains Sam Altman who was formerly the president of Y Combinator.

If this all seems a little far-fetched, there may be an explanation: “There’s a billion to one chance we’re living in base reality,” Musk said onstage in 2016. Musk has apparently done a great deal of thought about the possibility that we’re all living in a simulation, and “my brother and I agreed that we would ban such conversations if we were ever in a hot tub.” The notion of a “base reality” may be a reference to a 2003 hypothesis put forward by philosopher Nick Bostrom, though it appears a bit more certain than Bostrom’s line of thought. It is a view echoed by some computer scientists, though the most effective rebuttal I’ve seen is, essentially, “well, so what if we are? This is a distinction without a difference.”

Musk also poured $2 million into a satire company, Thud. In March 2018, Musk announced the venture on Twitter with some former Onion staffers on board who said at the time, “We can confirm that we have learned nothing from prevailing trends in media and are launching a brand-new comedy project.” By December 2018, however, Musk told the group that no further funding would come from him; the group then had six months to launch and figure out a monetization strategy before the money ran out. Ambitious projects, like DNA Friend, a 23andMe satire, were quickly rushed out the door. Thud was shuttered in May.

In somewhat less amusing news, Musk also stood trial for defamation in December 2019. The suit was brought by Vernon Unsworth who helped rescue a soccer team and their coach who’d been trapped in a cave in Thailand. Musk had also attempted to assist with the rescue, by building a “minisub,” with the notion that it could be used to ferry the children from the cave. In an interview with CNN, Unsworth said the tube was a “PR stunt” with “absolutely no chance of working” and that Musk could “stick his submarine where it hurts.” (Musk’s lawyers would later pressure Unsworth to apologize for some of the comments he made in this interview during the suit.) Musk then called him a “pedo guy” on Twitter.

Musk apologized for and deleted the tweets, but Unsworth felt he’d been defamed. In a week-long trial in Los Angeles, both men laid out their cases; Musk won. That weekend, he celebrated by going to celebrity hot spot Nobu in his Cybertruck prototype with his girlfriend, pop star Grimes.

There’s probably some stuff I’ve missed here, but that’s just because there’s so much stuff. It does seem, looking back, that the pace began to accelerate around 2015. One question I get most often about Musk — from friends, family members, neighbors, and my editors — is “Okay, but is this dude for real?” Well, the rockets are real, the cars are real, the Not-A-Flamethrower is real, and so is the tunnel starting in the SpaceX parking lot. The lawsuits are varying degrees of real. The timelines Musk gives himself on the products he makes are almost always wishful thinking, and not all of his ideas work in reality.

For most of the rest of it, your guess is as good as mine. It may turn out that he was serious about that volcano lair after all. Because with Musk, the spectacle is also the point: he’s not just a CEO; he’s an influencer. I mean, he smoked weed on The Joe Rogan Experience; beefed with the president, the press, and Azealia Banks; spent time taunting his haters; and sent his Roadster into space and then live-streamed it.

The rise of the social media influencer as a new form of celebrity in the 2010s seems to have suited Musk. He’s leaned heavily on YouTubers and, like many other influencers before him, engaged in a popular crossover event. He has a devoted army of fans, just like Taylor Swift or PewDiePie. Like most influencers, he seems to enjoy spectacle. And also like most influencers, he’s used social media — and his own celebrity — as a valuable form of marketing. That’s especially important for Tesla (which has arguably become the car brand for YouTubers) since Tesla doesn’t engage in paid advertisements. Sure, some Elon activity is decidedly spontaneous, but even that works in favor of the marketing since it makes his fans feel closer to him. I mean, how many big-deal CEOs besides Musk tweet about Rick and Morty, or engage with random followers? To borrow a turn of phrase from Jay Z: Elon Musk isn’t just a businessman; he’s a business, man.

Musk seems unlikely to stop Elonning anytime soon. We do not yet have the technology to predict cycles of Elon activity, thus allowing us to forecast heavy Elon seasons. I sincerely hope someone is working on this, but, until then, I suppose we’d all better keep an eye on his Twitter account: he appears more often there than anywhere else.