When I told readers that January would be “back to basics” month at Get Rich Slowly, the number-one request I received was to write about how to invest.

Rather than scatter investing info throughout the month, I decided to collect the essentials into one mammoth article. Here it is: all you need to know about how to invest — even if you’re a beginner.

In writing this article, I tried not to bog it down with jargon and definitions. (I’m sure I let some of that slip through the cracks, though. I apologize.) Nor did I dive deep. Instead, I aimed to share the basic info you need to get started with investing.

What follows are eight simple rules for how to invest. And in the end, I’ll show you how to put these rules into practice. First, let’s dispel some popular misconceptions.

Investing isn’t Gambling — and It isn’t Magic either

Investing scares many people. The subject seems complicated and mysterious, almost magical. Or maybe it seems like gambling. When the average person meets with his financial adviser, it’s often easiest to sit still, smile, and nod.

One of the problems is that the investing world is filled with jargon. What are commodities? What’s alpha? An expense ratio? How do bonds differ from stocks? And sometimes, familiar terms – such as risk – mean something altogether different on Wall Street than they do on Main Street.

Plus, we’re bombarded by conflicting opinions. Everywhere you look, there’s a financial expert who’s convinced she’s right. There’s a never-ending flood of opinions about how to invest, and many of them are contradictory. One guru says to buy real estate, another says to buy gold. Your cousin got rich with Bitcoin. One pundit argues that the stock market is headed for record highs, while her partner says we’re due for a “correction”. Who should you believe?

Perhaps the biggest problem is complexity – or perceived complexity. To survive and seem useful, the financial services industry has created an aura of mystery around investing, and then offered itself as a light in the darkness. (How convenient!) As amateurs, it’s easy to buy into the idea that we need somebody to lead us through the jungle of finance.

Here’s the truth: Investing doesn’t have to be difficult. Investing is not gambling, and it’s not magic.

You are perfectly capable of learning how to invest. In fact, it’s likely that — even if you know nothing right now — you can earn better investment returns than 80% of the population without any scammy tricks or expensive tips sheets.

Today, I want to convince you that if you keep things simple, you can do your own investing and receive above-average returns – all with a minimum of work and worry. Sound good? Great! Let’s learn how to invest.

Table of Contents

- Investing rule #1: Get started

- Investing rule #2: Think long-term

- Investing rule #3: Spread the risk

- Investing rule #4: Keep costs low

- Investing rule #5: Keep it simple

- Investing rule #6: Make it automatic

- Investing rule #7: Ignore the noise

- Investing rule #8: Conduct an annual review

Investing Rule #1: Get Started

The first thing you need to know about investing is that you should start today. It doesn’t matter how much money you have. What matters is getting started — then making it a habit. There are many investment apps out there that make investing easier than ever.

“The amount of [money] you start with is not nearly as important as getting started early,” writes Burton Malkiel in The Random Walk Guide to Investing, which is an excellent beginner’s book on how to invest. “Procrastination is the natural assassin of opportunity. Every year you put off investing makes your ultimate retirement goals more difficult to achieve.”

The secret to getting rich slowly, he says, is the extraordinary power of compound interest. Given enough time, even modest stock market gains can generate real wealth.

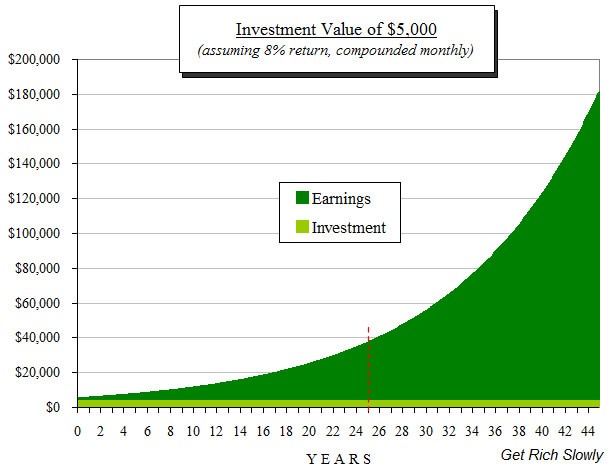

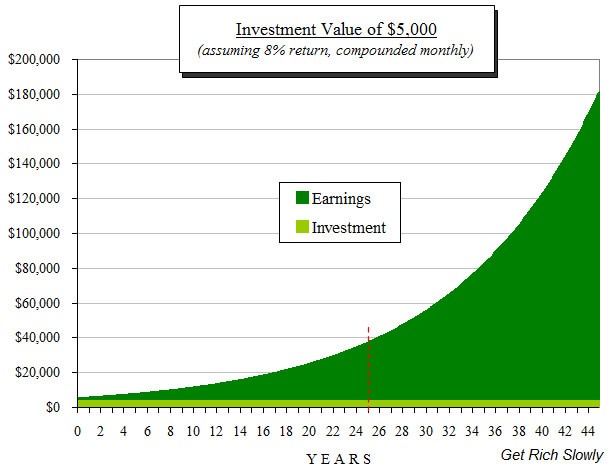

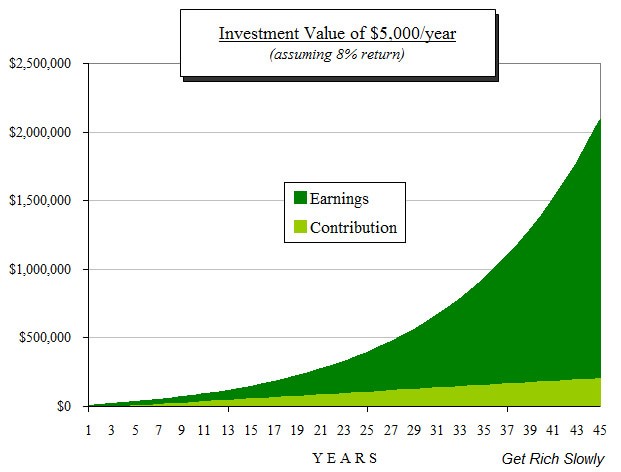

As you’ll recall from your junior high math class, compounding is the snowball-like growth that occurs as the interest (or other return) from an investment generates more interest. Let’s look at some examples.

- If you make a one-time contribution of $5000 to a retirement account and receive an 8% annual return, you’ll earn $400 during the first year, giving you a total of $5400.

- During the second year, you’ll receive 8% not only on the initial $5000, but also on the $400 in investment returns from the first year, for total earnings of $432.

- In the third year, you’ll earn returns of $466.56. And so on.

After ten years of receiving an 8% annual return, your initial $5000 will have more than doubled to $10,794.62!

Compounding is powerful, but it needs time to work its magic. The longer you wait to begin investing, the less time your money has to grow.

Assume you a one-time $5000 contribution to your retirement account at age twenty. And assume that your account somehow manages to earn an 8% annual return every year. If you never touch the money, your $5000 will grow to $159,602.25 by the time you’re 65 years old. But if you wait until you’re forty to make that single investment, your $5000 would only grow to $34,242.38.

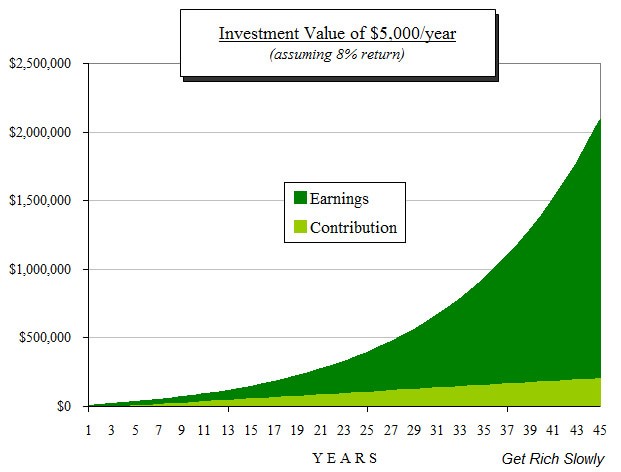

The power of compounding can be accentuated through regular investments. It’s great that a single $5000 investment can grow to nearly $160,000 in 45 years, but it’s even more exciting to see what happens when you make saving a habit. If you were to invest $5000 annually for 45 years, and if you left the money to earn an 8% annual return, your savings would total over $1.93 million. A golden nest egg indeed! You’d have more than eight times the amount you contributed.

This is the power of compounding.

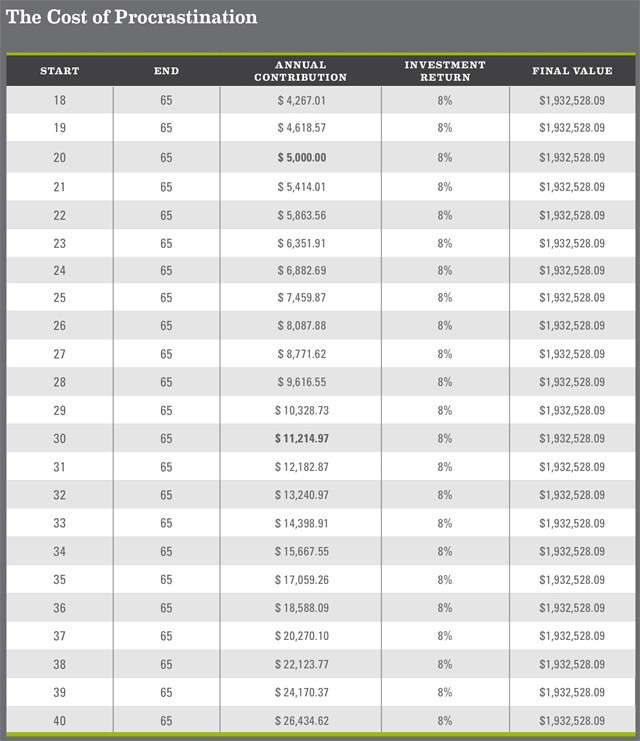

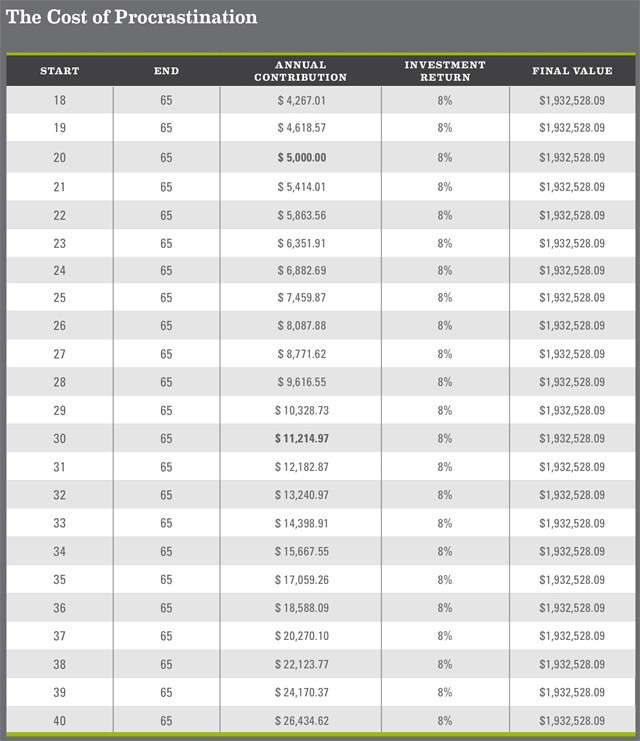

It’s human nature to procrastinate. A lot of people put off investing for retirement (and other goals) because they get distracted by the demands of daily life. (Studies show that only about half of Americans have money in the stock market.) “I can start saving next year,” they tell themselves. But the costs of delaying are enormous. Even one year makes a difference.

The following chart illustrates the cost of procrastination.

If, starting when you’re twenty, you invest $5000 per year and receive an 8% return, your account would have $1,932,528.09 when you’re 65 years old. But if you wait even five years, you’d have to increase your annual contributions to nearly $7500 to have that same amount by age 65. And if you were to wait until you were forty to begin investing, you’d have to contribute over $25,000 per year to hit the same target!

When investing, time is your friend. Start as soon as you can. Tomorrow is good. Today is better. (You can’t invest yesterday, so now will have to do.)

True story: For a brilliant example of compounding in real life, turn to American statesman Benjamin Franklin. When he died in 1790, Franklin left the equivalent of $4400 to each of two cities, Boston and Philadelphia. But his gift came with strings attached. The money had to be loaned out to young married couples at five percent interest. What’s more, the cities couldn’t access the funds until 1890 – and they couldn’t have full access until 1990. Two hundred years later, Franklin’s $8800 bequest had grown to more than $6.5 million between the two cities! True story.

Investing Rule #2: Think Long-Term

A lot of people have the mistaken idea that investing requires following daily stock market movement, then buying and selling stocks frequently. That’s how it’s done in the movies, but you know what? People who invest like that actually tend to make less than the people who do nothing. I’m not making this up.

Smart investing is a waiting game.

It takes time – think decades, not years – for compounding to do its thing. But there’s another reason to take the long view.

In the short term, investment returns fluctuate. The price of a stock might be $90 per share one day and $85 per share the next. And a week later, the price could soar to $120 per share. Bond prices fluctuate too, albeit more slowly. And yes, even the returns you earn on your savings account change with time. (High-interest savings accounts yielded five percent annually in the U.S. just a few years ago; today, the best savings accounts yield about 1.5%.)

Short-term returns aren’t an accurate indicator of long-term performance. What a stock or fund did last year doesn’t tell you much about what it’ll do during the next decade.

In Stocks for the Long Run, Jeremy Siegel analyzed the historical performance of several types of investments. Siegel’s research showed that, for the period between 1926 and 2006 (when he wrote the book):

- Stocks produced an average real return (or after-inflation return) of 6.8% per year.

- Long-term government bonds produced an average real return of 2.4%.

- Gold produced an average real return of 1.2%.

My own calculations – and those of Consumer Reports magazine – show that real estate returns even less than gold over the long term.

Although stocks tend to provide handsome returns over the long term, they come with a lot of risk in the short term. From day to day, the price of any given stock can rise or fall sharply. Some days, the price of many stocks will rise or fall sharply at the same time, causing wild movement in entire stock-market indexes.

Even over one-year time spans, the stock market is volatile. While the average stock-market return over the past 80 years was about 10% (about 7% after inflation), the actual return in any given year can be much higher or lower. In 2008, U.S. stocks dropped 37%; in 2013, they jumped over 32%.

Here’s a table showing the rise and fall of the S&P 500 index over a fifteen-year timespan. Looks like a roller coast, right?

![Note that my source for this data is Wikipedia, which may or may not be a good thing. [S&P 500 Annual Returns]](https://wallstreetprobe.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/How-to-invest-An-essential-guide-for-beginners-Get-Rich-Slowly-2.png)

During any one-year period, stocks will outperform bonds only 60% of the time. But over ten-year periods, that number jumps to 80%. And over thirty years, stocks almost always win.

Despite the stock market’s ongoing wins, the average person almost always underperforms the market as a whole. Even investment professionals tend to underperform the market.

During the 20-year period ending in 2012, the S&P 500 returned an average 8.21%. The average investor in stock-market mutual funds only earned 4.25%. Why? Because they tended to panic and sell when prices dropped, and then bought back in as prices rose – just the opposite of the “buy low, sell high” advice we’ve all heard.

Investing is a game of years, not months.

Don’t let wild market movements make you nervous. And don’t let them make you irrationally exuberant either. What your investments did this year is far less important than what they’ll do over the next decade (or two, or three). Don’t let one year panic you, and don’t chase after the latest hot investments. Stick to your long-term plan.

Investing Rule #3: Spread the Risk

While the stock market as a whole returns a long-term average of ten percent per year, individual stocks experience drastically different fortunes. In 2013, the S&P 500 index grew 29.60%. But some of the 500 companies that made up the index did much better than others. Stock in Netflix (NFLX) soared 297.06%. Best Buy (BBY) was up 237.64% and Delta Airlines up 130.33%. Meanwhile, Newmont Mining (NEM) dropped 51.16% and Teradata (TDC) fell 27.18%.

To smooth the market’s wild ups and downs, smart investors spread their money around. Surprisingly, studies show that while diversification reduces risk, it doesn’t affect average performance much — if at all. (For more info, check out this guide to diversification from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.)

Buying individual stocks isn’t really investing — it’s gambling. I know this from experience. In the past, I thought I could outsmart the market. In 2000, enamored by the PalmPilot, I bought shares of the company that made the devices. I paid close to $90 per share. Just over a year later, the shares had lost 90% of their value. (I made similar mistakes with The Sharper Image and Countrywide Financial.)

By owning more than one stock, you reduce your risk. If you have ten stocks and one of them tanks, the damage isn’t as bad because you still own nine others. True, you don’t reap all of the rewards if a stock skyrockets like Netflix did in 2013, but the smoother ride is generally worth it.

Investors also reduce risk by owning more than one type of investment. As we’ve seen, over the long term stocks are better investments than bonds or gold or real estate. But over the short term, stocks only outperform bonds about two-thirds of the time. Because the prices of stocks and bonds move independently of each other, investors can reduce risk by owning a mix of both.

One popular guideline is to base how much you put into bonds on your age. If you’re 35 years old, put 35% into bonds and 65% into stocks. If you’re 53, put 53% into bonds and 47% into stocks. This is a fine starting point for the average investor.

One of the best ways to spread risk when investing is through the use of mutual funds.

Mutual funds are collections of investments. They let people like you and me pool our money to buy small pieces of many companies all at once. Imagine, for instance, the hypothetical Awesome Fund, which invests in fifty different stocks and ten different corporate bonds. By buying one share of the Awesome Fund, You, Inc. would have a piece of sixty different investments. If one goes bust, the damage is minimized.

Mutual funds make diversification easy by letting you own shares in many companies at once. Plus, when you own a mutual fund, somebody else does the research and buys and sells the stocks so you don’t have to.

Because mutual funds offer great advantages to individual investors, they’ve soared in popularity over the past 30 years. But they’re not without drawbacks.

Investing Rule #4: Keep Costs Low

The biggest drawback to mutual funds is their cost. With stocks and bonds, you usually only pay when you buy and sell. But with mutual funds, there are ongoing costs built into the funds. (You don’t pay these costs directly; instead, they’re subtracted from the fund’s total return.) Some of these costs are obvious, but others aren’t.

All together, mutual-fund costs typically run about 2% annually. So for every $1,000 you invest in mutual funds, $20 gets taken out of your return each year. (On average.) This may not seem like much, but 2% is huge when it comes to investments.

In fact, according to a 2002 study by Financial Research Corporation, the best way to predict a mutual fund’s future performance was to compare its expense ratio with similar funds. Mutual funds with lower fees tend to have better performance. Again and again, other studies have found the same thing.

In his book Your Money & Your Brain, Jason Zweig notes:

“Decades of rigorous research have proven that the single most critical factor in the future performance of a mutual fund is that small, relatively static number: its fees and expenses. Hot performance comes and goes, but expenses never go away.”

There are a couple of reasons mutual funds are so expensive.

- First, most funds are run by a team of people who research opportunities, buy and sell individual investments, and do other work necessary to maintain the fund. These “actively managed” funds subtract their operating costs from whatever money they earn (or lose) for their investors.

- Many funds also carry a “load”, which is a one-time sales charge or commission. These loads are generally around five percent. Think about that. When you purchase a mutual fund with a load, you’re basically agreeing to handicap yourself by five percent before you even begin to run the investment race. That doesn’t sound like a smart investment to me!

Fortunately, there’s an alternative to these expensive actively managed funds. Some funds are “passively managed”.

Passively managed funds – also called index funds – try to mimic the performance of a specific benchmark, like the Dow Jones Industrial Average or S&P 500 stock-market indexes. Because these funds try to match (or index) a benchmark and not beat it, they don’t require much intervention from the fund manager and her staff, which means their costs are much lower.

The average actively managed mutual fund has a total of about 2% in costs, whereas a typical passive index fund’s costs average only about 0.25%. So, to come out ahead on a passively managed fund, the average fund manager doesn’t just have to beat his benchmark index — he has to beat it by 1.75%! And since both types of funds — active and passive — earn market-average returns before expenses, investors who own actively managed funds typically earn 1.75% less than those who own index funds!

Although this 1.75% difference in costs between actively and passively managed mutual funds may not seem like much, there’s a growing body of research that says it makes a huge difference in long-term investment results.

Further reading: If you’re a math nerd and want to see all the calculations and proof as to why index funds do better than actively-managed fund, check out this short (but dense) paper from Stanford professor William Sharpe: “The Arithmetic of Active Management”.

Investing Rule #5: Keep It Simple

Index funds offer another great advantage for individual investors like you and me.

Instead of owning maybe twenty or fifty stocks, an index fund owns the entire market. (Or, if it’s an index fund that tracks a specific portion of the market, they own that portion of the market.) For example, an index fund like Vanguard’s VFINX, which attempts to track the S&P 500 stock-market index, owns all of the stocks in S&P 500 and in the same proportions as they exist in the market.

The bottom line is this: The only investments you need to hold are index funds. They provide lower risk, lower costs, and lower taxes than stocks or actively managed mutual funds. Yet they provide the same returns as the market as a whole.

I’m not the only one who believes this. Over the past twenty years, many intelligent investors have come to this same conclusion. In fact, the greatest investor of all time — Warren Buffett — has publicly and repeatedly argued that 99% of people should be invested in index funds.

Still, there many different index funds from which to choose. Plus, how many should you own? As always, it pays to keep things simple.

One good way to get started is to use a lazy portfolio, a balanced collection of index funds designed to do well in most market conditions with a minimum of fiddling from you. Think of them as recipes: A basic bread recipe contains flour, water, yeast, and salt, but you can build on it to get as elaborate as you’d like.

This two-fund portfolio from financial columnist Scott Burns may be the simplest way to achieve balance. He calls it his “couch potato portfolio”. It’s evenly split between stocks and bonds:

- 50% Vanguard 500 Index (VFINX)

- 50% Vanguard Total Bond Market Index (VBMFX)

Burns has also created a “couch potato cookbook” that lists several different lazy portfolios and answers some common questions.

In his book How a Second Grader Beats Wall Street, Allan Roth (no relation to your humble author) explains how he taught his son how to invest. He used this lazy portfolio:

- 40% Vanguard Total Bond Market Index (VBMFX)

- 40% Vanguard Total Stock Market Index (VTSMX)

- 20% Vanguard Total International Stock Index (VGTSX)

This is the medium-risk version of Roth’s second-grader portfolio. For higher risk, you’d put 10% into bonds, 60% into American. stocks, and 30% into international stocks. A lower-risk allocation would be 70% in bonds, 20% in American stocks, and 10% in foreign stocks.

Though I’m a passive investor, I don’t actually use a lazy portfolio. But if I were to use one, it’d follow three simple rules. First, I’d want the bond portion to equal my age. Second, I’d want 10% in real estate to spread risk a little more. And third, I’d want the stock portion to be two-thirds American stocks and one-third international stocks. Since I’m 48 years old, it’d look like this:

- 48% Vanguard Total Bond Market Index (VBMFX)

- 28% Vanguard Total Stock Market Index (VTSMX)

- 14% Vanguard Total International Stock Index (VGSTX)

- 10% Vanguard REIT Index (VGSIX)

This lazy portfolio changes with your age, which I like. It takes on more risk when you’re younger and then eases into bonds as you get older.

These are just a few suggestions. There are scores of index funds out there, and countless ways to build portfolios around them. In fact, there’s a subculture of investors who love lazy portfolios. You can read more about lazy portfolios at sites like Bogleheads and Marketwatch.

There’s no one right approach to index-fund investing. Yes, it’s simple, but you can spend a long time deciding which asset allocation is right for you. While it’s important to do the research and educate yourself, you probably shouldn’t spend too much time sweating over which choice is “best.” Just pick one and get started. You can always make changes later.

Investing Rule #6: Make It Automatic

After you’ve set up your investment account, it’s time to remove the human element from the equation. As always, you should do what it can to automate good behavior.

If you plan to do all your investing through your employer’s retirement plan, it’s easy to get started. Contact HR to have retirement contributions automatically taken out of your paycheck. You should at least contribute as much as your employer matches. But remember: The more you contribute, the sooner you’ll reach the goals in your personal action plan. Funnel as much profit as possible into investing for the future.

Many company plans don’t offer index funds. In that case, find funds that have low costs and are widely diversified. So-called lifecycle or “target-date” funds are often an okay backup option. If your employer-sponsored plan doesn’t offer a lot of choices, ask HR if it’s possible to get more. They might say “no,” but then again, they might expand the company’s menu of mutual funds. It never hurts to ask!

If you plan to invest on your own — whether instead of or in addition to investing through your company’s plan — contact the mutual fund companies directly instead of going through a broker. Three of the larger no-load mutual fund companies are:

If you’re just learning how to invest, you should probably pick one company and stick with it; that’ll make things easier because you’ll be able to track all your investments in one place. Vanguard is probably the most popular company for passive investors. Personally, I use Fidelity. T. Rowe Price is fine too.

For a more detailed discussion of how to automate your investing, pick up a copy of David Bach’s The Automatic Millionaire.

Investing Rule #7: Ignore the Noise

As you’re learning how to invest, one important skill to master is ignoring all of the noise. Ignore the news. Ignore your friends. Ignore everyone. Make a plan. Put that plan into action. Make it automatic. Then forget about it. Seriously, this is the secret to investing success.

People tend to pour money into stocks in the middle of bull markets — after the stocks have been rising for some time. Speculators pile on, afraid to miss out. Then they panic and bail out after the stock market has started to drop. By buying high and selling low, they lose a good chunk of change.

![God, I hate USA Today's market coverage... [USA Today Hyperbole]](https://wallstreetprobe.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/How-to-invest-An-essential-guide-for-beginners-Get-Rich-Slowly-21.jpg)

It’s better to buck the trend. Follow the advice of Warren Buffett, the world’s greatest investor: “Be fearful when others are greedy, and be greedy when others are fearful.”

In his 1997 letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders Buffett — the company’s chairman and CEO — made a brilliant analogy: “If you plan to eat hamburgers throughout your life and are not a cattle producer, should you wish for higher or lower prices for beef?” You want lower prices, of course: If you’re going to eat lots of burgers over the next 30 years, you want to buy them cheap.

Buffett completes his analogy by asking, “If you expect to be a net saver during the next five years, should you hope for a higher or lower stock market during that period?”

Even though they’re decades away from retirement, most investors get excited when stock prices rise (and panic when they fall). Buffett points out that this is the equivalent of rejoicing because they’re paying more for hamburgers, which doesn’t make any sense: “Only those who will [sell] in the near future should be happy at seeing stocks rise.” He’s driving home the age-old wisdom to buy low and sell high.

Following this advice can be tough. For one thing, it goes against your gut. When stocks have fallen, the last thing you want to do is buy more. Besides, how do you know the market is near its peak or its bottom? The truth is you don’t. The best solution is to make regular, planned investments — no matter whether the market is high or low.

Meanwhile, ignore the financial news.

In Why Smart People Make Big Money Mistakes, Gary Belsky and Thomas Gilovich cite a Harvard study of investing habits. The results?

“Investors who received no news performed better than those who received a constant stream of information, good or bad. In fact, among investors who were trading [a volatile stock], those who remained in the dark earned more than twice as much money as those whose trades were influenced by the media.”

Though it may seem reckless to ignore financial news, it’s not: If you’re saving for retirement 20 or 30 years down the road, today’s financial news is mostly irrelevant. So make decisions based on your personal financial goals, not on whether the market jumped or dropped today.

Investing Rule #8: Conduct an Annual Review

During a given year, some of your investments will have higher returns than others. For example, if you started the year with 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds, you may find that you now have 66% in stocks and 34% in bonds. What’s more, your goals may have changed, or you might discover you can’t stomach as much risk as you thought you could (this happened to a lot of folks in 2008).

To compensate, rebalance your investments at the end of each year. This simply means you should shift money around so your assets are allocated the way you want them to be. Doing this is another way to take the emotion out of investing.

There are two ways to rebalance.

- You can sell your winners and buy your losers. By selling the investments that have grown and buying those that lag behind, you’re buying low and selling high, just as you should. Be aware, though, that you might owe taxes if you go this route, so check out the tax implications before you sell any securities.

- If you can afford it, contribute new money to your investment account, but only to buy the assets that need to catch up. By doing this, you don’t have to worry about taxes, but you’ll need some cash on hand.

Though many investment professionals swear by rebalancing, there’s some research that shows it’s not as important as people once thought. In The Little Book of Common Sense Investing, John Bogle writes, “Rebalancing is a personal choice, not a choice that statistics can validate. There’s nothing the matter with doing it…but also no reason to slavishly worry about small changes…” In other words: Rebalance if your asset allocation is way out of line but don’t worry about small changes — especially if you’d end up paying a lot of fees by rebalancing.

The Bottom Line

In this article, you’ve learned that the stock market provides excellent long-term returns, and that you can do better than 95% of individual investors by putting your money into index funds. But how do you put this knowledge to work? What’s the best way to take advantage of the things you’ve learned?

The answer is shockingly simple: To get started investing, set up automatic investments into a portfolio of index funds. Here’s how:

- Put as much as you can into investment accounts – as soon as possible. Fund tax-advantaged accounts (such as retirement accounts) before taxable accounts.

- Invest in a low-cost stock index fund, such as Vanguard’s Total Stock Market Index Fund (VTSMX) or Fidelity’s Spartan Total Market Index Fund (FSTMX).

- If the stock market makes you nervous, or you want to spread the risk, put some of your money into a bond fund like Vanguard’s Total Bond Market Index Fund (VBMFX) or Fidelity’s Total Bond Market Index Fund (FTBFX).

- If you want diversification with less work, invest in a low-cost combo fund like Vanguard’s STAR Fund (VGSTX) or Fidelity’s Four-in-One Index Fund (FFNOX).

After that, ignore the news no matter how exciting or scary things get. Once a year, go through your investments to be sure your investments still match your goals. Then continue to put as much as you can into the market—and let time take care of the rest.

That’s it. That’s how to invest so that you earn great returns without stress and worry. Seriously. Do this and you should outperform most other individual investors over the long term.

This strategy isn’t just great for investing novices. Even market professionals endorse it. In his 2013 letter to shareholders, for instance, Warren Buffett outlined what will happen to his vast wealth when he dies. Most of it will go to charity; some will go to his wife. How will his wife’s money be handled?

“My advice to the trustee couldn’t be more simple: Put 10% of the cash in short-term government bonds and 90% in a very low-cost S&P 500 index fund. (I suggest Vanguard’s.) I believe the trust’s long-term results from this policy will be superior to those attained by most investors…”

Are there other investment strategies that might provide similar returns? Sure. But these approaches also require greater education, sophistication, and attention on the part of the investor.

Unless you know for a certainty that you have this knowledge, sophistication, and attention, you’re better off sticking with index funds.

Footnote: How I Invest

Do I practice what I preach? You bet! All of my money is in index funds and individual bonds. Here are my top four holdings as of today:

![My top four holdings are all Fidelity index funds [My Top Holdings]](https://wallstreetprobe.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/How-to-invest-An-essential-guide-for-beginners-Get-Rich-Slowly-22.jpg)

That gives me an overall asset allocation that looks like this:

![I'm perfectly content with this asset allocation [My Asset Allocation]](https://wallstreetprobe.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/How-to-invest-An-essential-guide-for-beginners-Get-Rich-Slowly-23.jpg)

I’m 48 years old and have 80% of my portfolio in stocks, 10% in bonds, and 10% in other investments. I do still own 1115 shares of now-worthless Sharper Image stock. I keep it to remind me of my past stupidity.

One of my personal goals over the next few years is to gain the knowledge and sophistication necessary to dabble in other forms of investing. (I believe I have the mindset already.) For now, I’m content heeding Warren Buffett’s advice. It’s served me well.

In 2006, J.D. founded Get Rich Slowly to document his quest to get out of debt. Over time, he learned how to save and how to invest. Today, he’s managed to reach early retirement! He wants to help you master your money — and your life. No scams. No gimmicks. Just smart money advice to help you reach your goals.

Click here to see the full story

![Note that my source for this data is Wikipedia, which may or may not be a good thing. [S&P 500 Annual Returns]](https://wallstreetprobe.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/How-to-invest-An-essential-guide-for-beginners-Get-Rich-Slowly-2.png)

![God, I hate USA Today's market coverage... [USA Today Hyperbole]](https://wallstreetprobe.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/How-to-invest-An-essential-guide-for-beginners-Get-Rich-Slowly-21.jpg)

![My top four holdings are all Fidelity index funds [My Top Holdings]](https://wallstreetprobe.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/How-to-invest-An-essential-guide-for-beginners-Get-Rich-Slowly-22.jpg)

![I'm perfectly content with this asset allocation [My Asset Allocation]](https://wallstreetprobe.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/How-to-invest-An-essential-guide-for-beginners-Get-Rich-Slowly-23.jpg)