The rise of the financial machines

THE JOB of capital markets is to process information so that savings flow to the best projects and firms. That makes high finance sound simple; in reality it is dynamic and intoxicating. It reflects a changing world. Today’s markets, for instance, are grappling with a trade war and low interest rates. But it also reflects changes within finance, which constantly reinvents itself in a perpetual struggle to gain a competitive edge. As our Briefing reports, the latest revolution is in full swing. Machines are taking control of investing—not just the humdrum buying and selling of securities, but also the commanding heights of monitoring the economy and allocating capital.

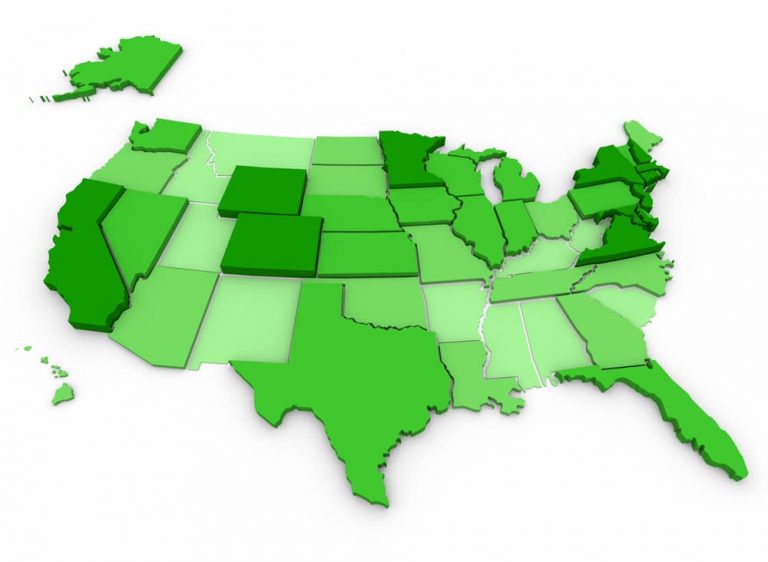

Funds run by computers that follow rules set by humans account for 35% of America’s stockmarket, 60% of institutional equity assets and 60% of trading activity. New artificial-intelligence programs are also writing their own investing rules, in ways their human masters only partly understand. Industries from pizza-delivery to Hollywood are being changed by technology, but finance is unique because it can exert voting power over firms, redistribute wealth and cause mayhem in the economy.

Because it deals in huge sums, finance has always had the cash to adopt breakthroughs early. The first transatlantic cable, completed in 1866, carried cotton prices between Liverpool and New York. Wall Street analysts were early devotees of spreadsheet software, such as Excel, in the 1980s. Since then, computers have conquered swathes of the financial industry. First to go was the chore of “executing” buy and sell orders. Visit a trading floor today and you will hear the hum of servers, not the roar of traders. High-frequency trading exploits tiny differences in the prices of similar securities, using a barrage of transactions.

In the past decade computers have graduated to running portfolios. Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and mutual funds automatically track indices of shares and bonds. Last month these vehicles had $4.3trn invested in American equities, exceeding the sums actively run by humans for the first time. A strategy known as smart-beta isolates a statistical characteristic—volatility, say—and loads up on securities that exhibit it. An elite of quantitative hedge funds, most of them on America’s east coast, uses complex black-box mathematics to invest some $1trn. As machines prove themselves in equities and derivatives, they are growing in debt markets, too.

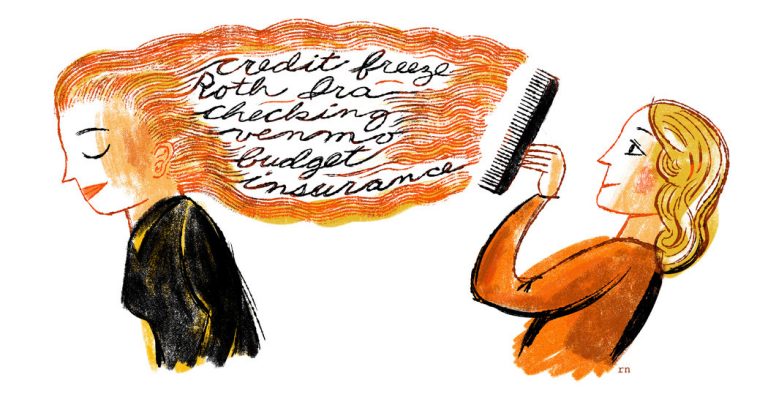

All the while, computers are gaining autonomy. Software programs using AI devise their own strategies without needing human guidance. Some hedgefunders are sceptical about AI but, as processing power grows, so do its abilities. And consider the flow of information, the lifeblood of markets. Human fund managers read reports and meet firms under strict insider-trading and disclosure laws. These are designed to control what is in the public domain and ensure everyone has equal access to it. Now an almost infinite supply of new data and processing power is creating novel ways to assess investments. For example, some funds try to use satellites to track retailers’ car parks, and scrape inflation data from e-commerce sites. Eventually they could have fresher information about firms than even their boards do.

Until now the rise of computers has democratised finance by cutting costs. A typical ETF charges 0.1% a year, compared with perhaps 1% for an active fund. You can buy ETFs on your phone. An ongoing price war means the cost of trading has collapsed, and markets are usually more liquid than ever before. Especially when the returns on most investments are as low as today’s, it all adds up. Yet the emerging era of machine-dominated finance raises worries, any of which could imperil these benefits.

One is financial stability. Seasoned investors complain that computers can distort asset prices, as lots of algorithms chase securities with a given characteristic and then suddenly ditch them. Regulators worry that liquidity evaporates as markets fall. These claims can be overdone—humans are perfectly capable of causing carnage on their own, and computers can help manage risk. Nonetheless, a series of “flash-crashes” and spooky incidents have occurred, including a disruption in ETF prices in 2010, a crash in sterling in October 2016 and a slump in debt prices in December last year. These dislocations might become more severe and frequent as computers become more powerful.

Another worry is how computerised finance could concentrate wealth. Because performance rests more on processing power and data, those with clout could make a disproportionate amount of money. Quant investors argue that any edge they have is soon competed away. However, some funds are paying to secure exclusive rights to data. Imagine, for example, if Amazon (whose boss, Jeff Bezos, used to work for a quant fund) started trading using its proprietary information on e-commerce, or JPMorgan Chase used its internal data on credit-card flows to trade the Treasury bond market. These kinds of hypothetical conflicts could soon become real.

A final concern is corporate governance. For decades company boards have been voted in and out of office by fund managers on behalf of their clients. What if those shares are run by computers that are agnostic, or worse, have been programmed to pursue a narrow objective such as getting firms to pay a dividend at all costs? Of course humans could override this. For example, BlackRock, the biggest ETF firm, gives firms guidance on strategy and environmental policy. But that raises its own problem: if assets flow to a few big fund managers with economies of scale, they will have disproportionate voting power over the economy.

Hey Siri, can you invest my life savings?

The greatest innovations in finance are unstoppable, but often lead to crises as they find their feet. In the 18th century the joint-stock company created bubbles, before going on to make large-scale business possible in the 19th century. Securitisation caused the subprime debacle, but is today an important tool for laying off risk. The broad principles of market regulation are eternal: equal treatment of all customers, equal access to information and the promotion of competition. However, the computing revolution looks as if it will make today’s rules look horribly out of date. Human investors are about to discover that they are no longer the smartest guys in the room. ■