IBM’s Watson Was Supposed to Change the Way We Treat Cancer. Here’s What Happened Instead.

IBM corporate headquarters in Armonk, New York.

STAN HONDA/Getty Images

What if artificial intelligence can’t cure cancer after all? That’s the message of a big Wall Street Journal post-mortem on Watson, the IBM project that was supposed to turn IBM’s computing prowess into a scalable program that could deliver state-of-the-art personalized cancer treatment protocols to millions of patients around the world.

Watson in general, and its oncology application in particular, has been receiving a lot of skeptical coverage of late; STAT published a major investigation last year, reporting that Watson was nowhere near being able to live up to IBM’s promises. After that article came out, the IBM hype machine started toning things down a bit. But while a lot of the problems with Watson are medical or technical, they’re deeply financial, too.

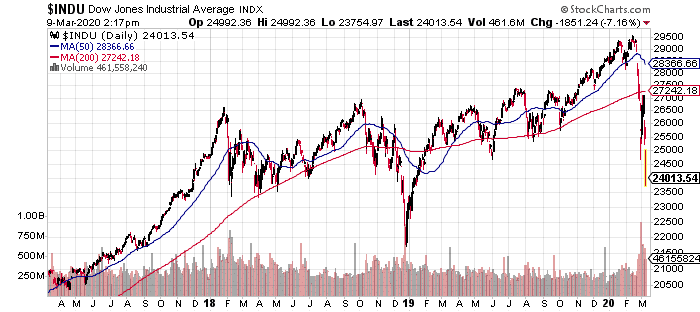

IBM is shrinking: In 2011, when the company first introduced the idea that Watson might be able to one day cure cancer, its revenues were $107 billion. They’ve gotten smaller every year since, ending up at $79 billion in 2017. That presents enormous problems for any CEO, who’s generally charged with growing the company, or, failing that, growing the stock price.

It’s very hard to keep a stock price growing in a company where revenues are falling, because those companies tend to be valued on a multiple of revenues—and that multiple itself will fall. If IBM went from being worth, say, 3 times revenues in 2011 to 2 times revenues in 2017, then its market capitalization would have shrunk by more than 50 percent.

This hasn’t happened, however, because IBM has to some degree counteracted the negative forces and kept its stock price steady through two main strategies. The first is communications: If you can persuade the markets that you’re going to get bigger rather than smaller, then your multiples will grow and your shares will rise. IBM pursued this strategy by hyping Watson long before it was really ready for prime time. If the markets believed that IBM was capable of curing cancer, then they would bid up the shares in the expectation of a major revenue boost in the near future.

The second strategy for shoring up a stock price in the face of declining revenues is basic financial engineering, in the form of share buybacks. If you buy back a large number of shares in the open market, then your share price can rise even as your market capitalization falls. The downside of that strategy is that the more money you spend on buybacks, the less money you have to invest in growth.

As the STAT article put it:

“IBM ought to quit trying to cure cancer,” said Peter Greulich, a former IBM brand manager who has written several books about IBM’s history and modern challenges. “They turned the marketing engine loose without controlling how to build and construct a product.”

Greulich said IBM needs to invest more money in Watson and hire more people to make it successful. In the 1960s, he said, IBM spent about 11.5 times its annual earnings to develop its mainframe computer, a line of business that still accounts for much of its profitability today.

If it were to make an equivalent investment in Watson, it would need to spend $137 billion. “The only thing it’s spent that much money on is stock buybacks,” Greulich said.

It’s not that IBM hasn’t invested boatloads in Watson; it has. But while six years and billions of dollars is a lot of time and money for a Silicon Valley startup, it’s a pretty normal expenditure in the world of medical trials, most of which fail.

What’s more, when it comes to artificial intelligence, IBM is competing with rivals like Amazon and Alphabet—companies that are still growing fast, that see no need to buy back their shares, and that similarly see no need to hype their A.I. achievements before they’re really ready for the spotlight. Watson is great at publicity stunts—no article about it is complete without the requisite mention of the time it won Jeopardy (even, it seems, this one)—but A.I. is a very tough nut to crack, and one where the top computer scientists are in incredibly high demand. Those scientists aren’t going to the company with the best press, they’re going to the companies with the best A.I., and the best science. Ask anybody in A.I. about Watson, and you’ll be told in no uncertain terms that they’re an also-ran in an incredibly competitive space.

The biggest hope for A.I. in oncology, then, is not that Watson is somehow going to get vastly better. Rather, it’s that Alphabet or someone else has been quietly building a game-changing A.I. without over-hyping it in advance. It’s still possible that A.I. might be able to do amazing things in the world of oncology. Just don’t expect those advances to come from Watson.