The authors Kristy Shen and Bryce Leung are part of a movement called Fire that encourages people to save intensively to retire early

Kristy Shen and Bryce Leung, authors of Quit Like a Millionaire, retired at 31 and 32, respectively

Photograph: Kristy Shen and Bryce Leung

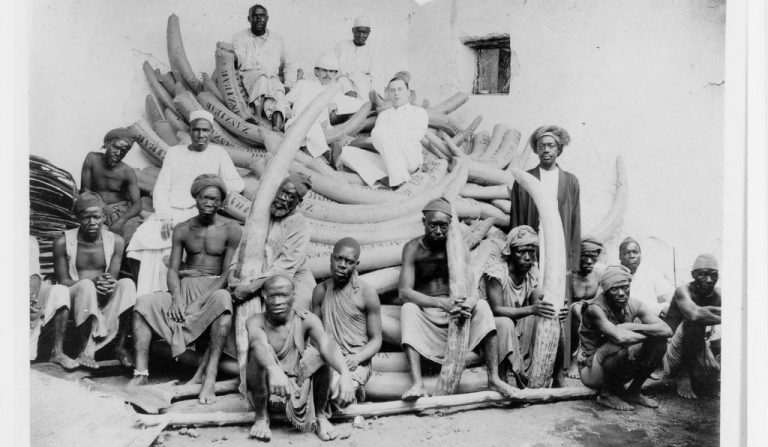

Growing up in poverty in rural China, where her family collectively lived on as little as $0.44 a day, Kristy Shen learned to make decisions based on pragmatism rather than passion from a young age.

On her first ever trip to a toy shop aged eight, after her family moved to Canada, she declined the offer of a teddy bear in favour of a cheaper one and requested that her father send the remainder of the money to their family in China. As a teenager, she chose to be a computer engineer, ignoring her dream to be a writer, based on a formula she devised to rank the best value university courses based on tuition fees versus future pay. And as an adult, any domestic disagreements with her husband, Bryce Leung, are generally won or lost based on who makes the best mathematical case.

But when, in 2012, Leung told her that in three years’ time their savings had the potential to hit C$1m (US$760,000) and they could retire in their early 30s, she was convinced the facts in front of her were incorrect. “My reaction was like, ‘No, this is wrong, your math is wrong, there’s something wrong here,’” she says. “I didn’t believe that was possible at all.”

In the end, of course, the most logical argument won. Three years later, Shen, then 31, and Leung, then 32, retired.

They are part of the growing Fire (financial independence retire early) movement that encourages workers to save intensively to enable them to stop working for money far earlier than is commonly done.

Today, at the grand old age of 36 and 37, respectively, Shen and Leung are reveling in their “retirement” (to use the term on two people so pulsating with youth seems disingenuous).

Since leaving their old jobs – they both worked as computer engineers – they have travelled the world almost constantly – spending time in countries including Japan, the UK, Portugal and Thailand – started a successful blog, Millennial Revolution, teaching others how to retire early too, and co-written two books. The first was a children’s book, Little Miss Evil. The second, Quit Like a Millionaire, a memoir-cum-how-to guide came out this month and presents financial independence as a route to happiness and is refreshingly dismissive of home ownership as an investment.

To begin with, their friends and families were skeptical, expecting them to return penniless after a year. But travelling cost them less than spending a year at home in Toronto, and their investment portfolio has grown since they left their old lives behind, so they now have more money than they started with. Some people, says Shen, see what they’re doing as “invalidating” because it challenges the status quo. “It really makes people question their lives and they don’t like that because it’s scary.”

Their journey to Fire started fairly conventionally – they were saving for a deposit to buy a house. But the more they saved, the more house prices went up and the less sure about getting on the property ladder they became. By 2012, after seven years of saving, they had C$500,000, but Leung started looking for other solutions. After coming across early Fire bloggers like Mr Money Mustache, he says: “I realised based on what they were doing and where we were that we could either be in debt for the next 25 years or retired in about three.”

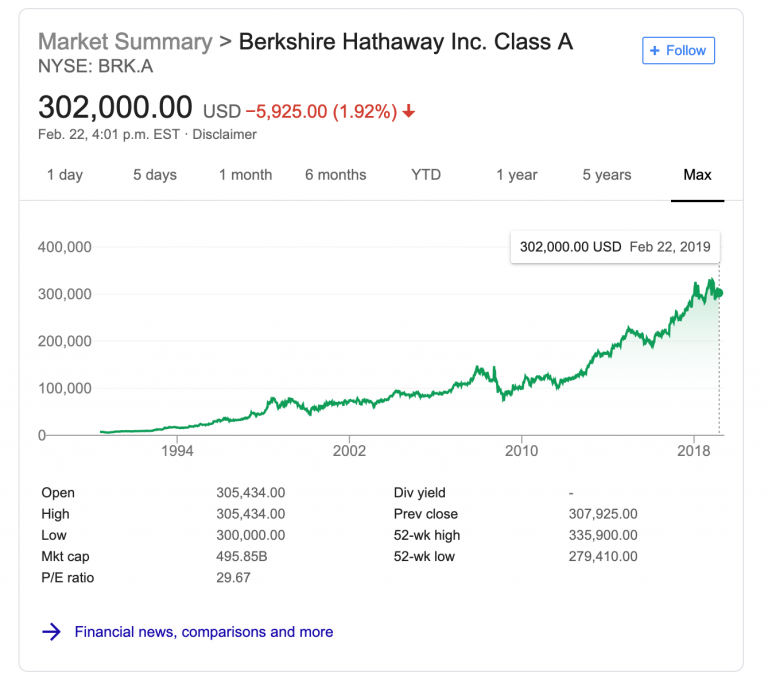

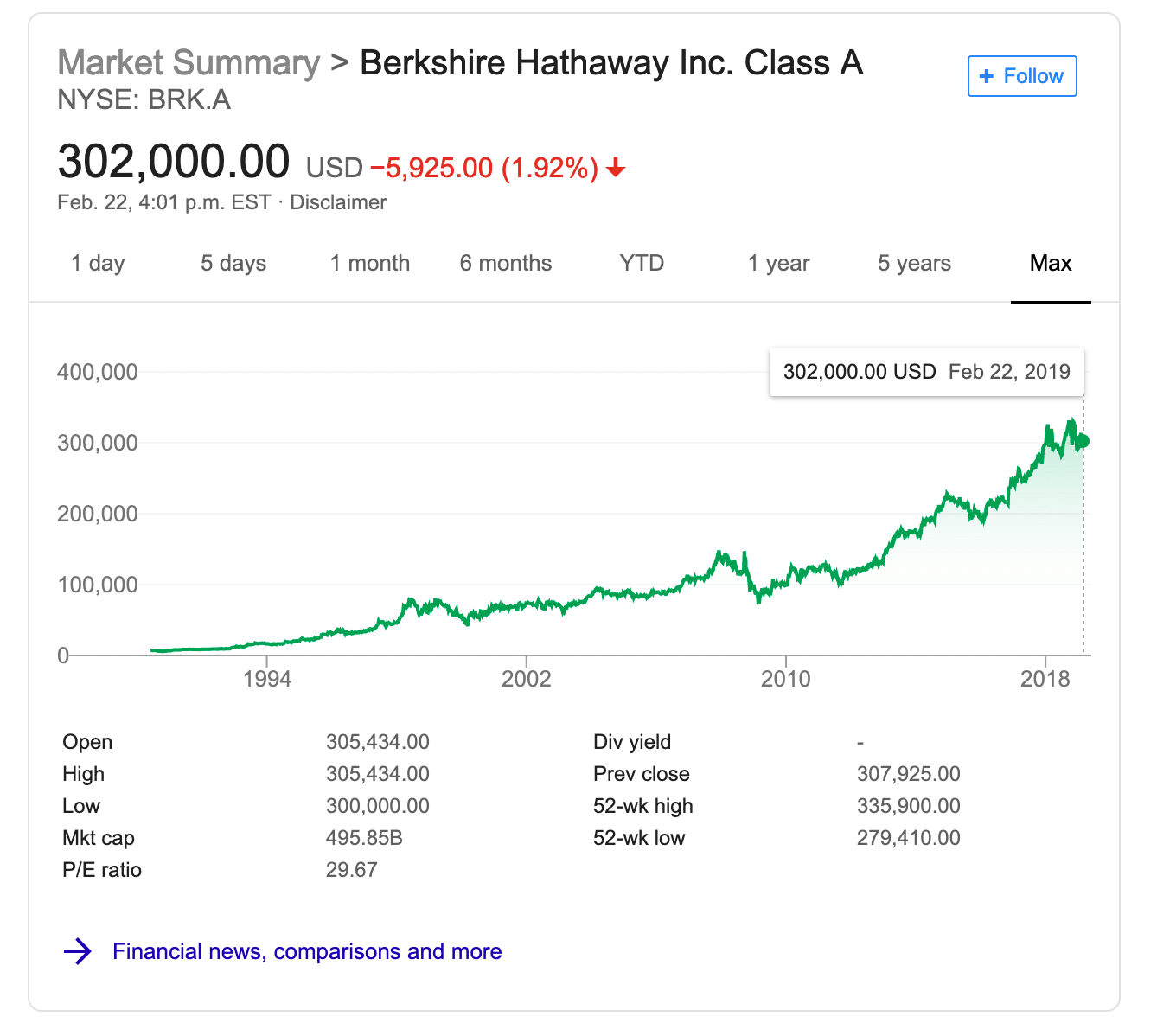

Using an adapted version of the “4% rule” – a principle borrowed from the traditional retirement world – they calculated their basic living expenses, C$40,000, and multiplied it by 25 to come to C$1m, the amount they would need to retire. In a total of nine years they managed to accrue around four-fifths of that in savings, plus a further C$200,000 through low-risk investments.

But their saving lifestyle wasn’t exactly frugal. They continued to spend money on holidays and even allowed for treats. Cuts were focused on three key areas: transportation, housing and food. They avoided eating out, only used public transport and car share services and lived away from downtown to save on rent. Tracking their spending helped to identify areas that they could cut back – including drinking habits. “At one point at the beginning, he was spending $400 just on beer,” says Shen, laughing. “I was like, ‘Do you realise this is how much we used to pay for rent at uni a month?’”

Now that they’re retired, they believe their savings, invested in low-cost index ETFs (exchange-traded funds), will keep them going for the foreseeable future. In case of disasters, including a 1929-style crash, they have three backup plans.

“We are probably some of the most pessimistic people you’ll ever meet,” says Leung, by way of explanation. “And we’re only doing this because we’ve created all these safety nets that will catch us.”

During her early childhood in Taiping, a village in Sichuan province, Shen says she learnt the scarcity mindset early on. “If you ever run out, the government is not here to help you, there’s never going to be any safety net to catch you. So my parents had instilled it in my head that money is the most important thing in the world.” As a student her father, who before she was born spent 10 years imprisoned in a labour camp, was able to visit Canada. Shen and her mother followed two years later.

Despite earning comparatively little money as a student and dishwasher, her parents sent money to China to support the rest of the family. Her early experiences in China gave Shen perspective on poverty, she says. “Basically, if you have four walls and you have your parents and you have food, you are wealthy.”

It’s a position of privilege to not be money-driven, she says. “Anybody that says ‘oh yeah, it’s only money’, ‘money comes and goes’, ‘it’s not about the money’, it’s like, you’ve never been poor.” If it hadn’t been for her childhood experiences, Shen doesn’t think she would be doing early retirement now. “I would’ve just thought just do something I love to do … I wouldn’t have thought put in the hard work now and get the gain later.”

Since retiring she is so much happier – at one point, her job made her so miserable she was on anxiety and depression medication – so much so that she wants to show others how to do it, too. She sees Fire as a remedy: “It’s almost like you see people get sick, you know what it feels like and it sucks to be sick and you want to give them the medication to help them feel better.”

Leung, meanwhile, says he was recently diagnosed as “obnoxiously happy” by a doctor. He is so convinced by the power of Fire that he thinks it could even have political ramifications. “[Donald] Trump’s rise to power was caused by economic fear, Brexit was caused by economic fear … If everybody was FI [financially independent], Trump wouldn’t have got elected.”

So would they ever go back to their old jobs? Shen giggles drily. “I don’t think I would be very useful as an employee any more.” She has, she says, become too open-minded to obediently follow instruction. “Once you’ve been out of the matrix, you can’t go back into the matrix,” she says soberly. “You’ve already seen too much.”